Difference Between Wet Aging and Dry Aging

Despite people’s mixed opinions regarding meat consumption for whatever reasons, there are still millions of foodies who crave for juicy, meaty steaks. If you’re craving a big fat steak, you’re probably not alone. So, if you’re a steak lover yourself, then you must know the steak you’re so overly fond of is divided into two camps when it comes to the best way to age beef: wet or dry. Traditionalists prefer the centuries-old method to tenderize meat called dry aging. Modernists will like the simpler, quicker method of wet aging, which is a new kid on the block and produces a much different steak than dry aging. Most beef sold today is wet aged.

Wet-aging is nothing like dry-aging but produces the same tenderizing and moisture-retaining flavor as dry-aging, but that’s about it. Dry-aging is backed by centuries-old tradition, while the majority of aged beef today is processed by the wet method. Whatever happens inside the muscle is the same regardless of whether the meat is wet aged or dry aged. And the aging takes place at much the same rate no matter the beef is dry aged or wet aged, and the result in terms of tenderness mostly remains the same in both the methods. But there are some notable differences associated with the two methods. Let’s take a good look at the two aging methods to better understand which one is better.

What is Dry-aging?

Dry aging is the traditional method used to tenderize meat in order to make it more flavorful. In dry-aging, either the entire carcass or large chunks of beef are hung from hooks in open air or spaced on open, perforated shelving at 32 to 34 degrees under carefully controlled moisture conditions. The meat is usually left hanging for ten days to around three weeks. During the first 24 hours or so the muscles use up all their energy and a number of irreversible cross-bridges form in the muscle. During aging, these bonds are not broken, but the whole internal structure of the muscle is fragmented into pieces. The enzymes attack its protein cells, making the meat softer and tender. Proper care must be taken during dry aging to preserve optimum levels of temperature, humidity, and air movement in the cooler.

What is Wet-aging?

Managed dry aging is relatively expensive and as a result, mass-market beef suppliers resort to wet-aging to save both time and money. Most packaged beef today is aged in its vacuum packaging, a process called wet aging. In this process, large or small cuts of beef are sealed in vacuum-packed polyethylene bags and allowed to age using the meat’s own juices. The meat is vacuum-packed straight after slaughter to prevent moisture and water loss, therefore maximizing profits for the producers. Trim loss after 21 days of wet aging is only 1% because microbial growth is slowed and oxidative rancidity is virtually eliminated in a vacuum. It produces meat which is fleshier and has a milder flavor. Wet aging results in the same tenderizing and moisture-retaining benefits as dry aging, but that’s about it.

Difference between Wet Aging and Dry Aging

Method

– Dry aging is the traditional method in which either the entire carcass or large chunks of beef are hung from hooks in open air or spaced on open, perforated shelving at 32 to 34 degrees under carefully controlled moisture conditions. The meat is usually left hanging for ten days to around three weeks. Wet aging is a relatively new method to tenderize meat in which large or small cuts of beef are sealed in vacuum-packed polyethylene bags and allowed to age using the meat’s own juices. The meat is vacuum-packed straight after slaughter to prevent moisture and water loss.

Cost

– The aging takes place at much the same rate whether the beef is dry aged or wet aged. But the cost of wet-aging is clearly lower than dry-aging because excess bone, connective tissue and fat have been removed, therefore maximizing profits for the producer. Because the bag remains sealed, there is no moisture loss and because oxygen is excluded, microbial growth is slowed and oxidative rancidity is virtually eliminated. In addition, the boxed beef takes up less room than swinging beef from hooks. Professionally managed dry aging is expensive compared to its wet counterpart.

Taste

– Wet aging produces a much different steak than dry aging, with a fleshier and milder flavor. But because there is no oxidation of fat in wet-aging, there is no development of funky flavors. Dry-aging, on the other hand, is generally described to boast the true beef flavor and it simply tastes much better, thus, it’s worth the extra investment. Wet-aged meat becomes drier after cooking because the excess water expands with heat, producing a tougher result and as a result, the all-important caramelization is lost, especially when it comes to steaks and roasting cuts.

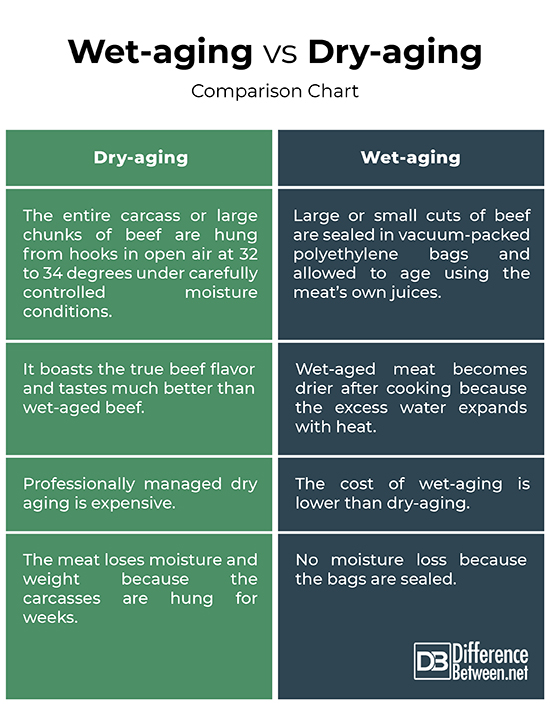

Wet-aging vs. Dry-aging: Comparison Chart

Summary of Wet-aging vs. Dry-aging

Aging greatly enhances the flavor and adds to the tenderness of the meat and the process starts immediately after the animal is slaughtered. When the meat is aging in a vacuum-sealed polyethylene bag, it is called “wet-aging” because the meat is not exposed to the air, resulting in less or no moisture loss, thereby maximizing profits for the producers. Dry-aging, on the other hand, is a more complex process where the carcass is split into hind quarters and front quarters and allowed to hang by hooks in a humidity-controlled cooler for about three to four weeks. Professionally managed dry-aged beef is expensive, so suppliers resort to wet-aging to save time and money. Regardless, dry aged meat tastes much better than wet-aged meat.

- Difference Between Caucus and Primary - June 18, 2024

- Difference Between PPO and POS - May 30, 2024

- Difference Between RFID and NFC - May 28, 2024

Search DifferenceBetween.net :

Leave a Response

References :

[0]López-Alt, J. Kenji. The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2015. Print

[1]Burg, Stanley P. Postharvest Physiology and Hypobaric Storage of Fresh Produce. Oxfordshire, UK: CABI Publishing, 2004. Print

[2]Hudson, Robert J. Animal and Plant Productivity. United Kingdom: EOLSS Publishers, 2010. Print

[3]Kelly, Dave, et al. Great Meat. Beverly, Massachusetts: Fair Winds Press, 2013. Print

[4]Image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dry_aging_beef.jpg

[5]Image credit: https://www.needpix.com/photo/490646/aging-meat-beef