Difference Between Ice Caps and Glaciers

Ice Caps

Ice caps are masses of ice that are less than 50,000 square kilometers in size. They are essentially domes that spread out laterally in all directions. They also tend to have a fairly flat topography.

Where are ice caps?

Ice caps are usually found in sub-polar to polar regions and at high elevation. An example of an ice cap is Vatnajokull in Iceland.

What is the difference between ice sheets and ice caps?

Ice sheets are masses of ice that are greater than 50,000 square kilometers in size. They are essentially larger versions of ice caps. The main difference between ice sheets and ice caps is size.

Where is the oldest ice on Earth found?

Ice caps and ice sheets contain incredibly old ice. The Allan Hills of Antarctica contain the oldest ice on Earth. The Allan Hills area is a blue ice region, where older layers tend to accumulate and become preserved. Blue ice regions are also famous for the meteorites that tend to be preserved there. The oldest ice drilled there is 2.7 million years old.

Glaciers

Glaciers are masses of ice which flow across the landscape in a pattern often similar to rivers.

Where are glaciers?

Glaciers will form in regions where it regularly snows during the winter and the snow does not completely melt during the summer. They are usually found near or within the polar regions and at high elevation.

How do glaciers form?

With each successive snowfall, the old snow beneath the newer snow layers will become more and more compacted over time until it becomes a granular icy sediment called firn. Eventually, the firn is compacted into a continuous body of ice. When a glacier becomes large enough, it will begin to move and deform under its own weight. This can be due to basal sliding, where ice at the bottom of the glacier is melting due to the pressure of overlying ice. This results in a slippery surface. The other way that glaciers move is through mechanical creep.

Glacier types

There are essentially two types of glaciers, alpine glaciers and ice sheet glaciers. Alpine glaciers will occur in mountainous regions and flow downhill. Alpine glaciers will deform the landscape as they flow, carrying rock, dirt, and other materials with them. Glaciers move slowly, but over long periods of time, they can be very destructive and transform landscapes. Alpine glaciers have carved valleys and lakes into mountain sides when given enough time. As a glacier moves, the material that builds up along its side is called a lateral moraine. The material that builds up along the middle of the glacier is the medial moraine. The material being pushed at the front of the glacier is called the terminal moraine.

Ice sheets can be much larger than alpine glaciers. They tend to flatten out the landscape and can cover entire continents. Examples of ice sheets include the Greenland ice sheet and the Antarctic ice sheet. There are also ice sheets which existed in the past which have since melted. North America and Europe, for example, were once covered in continental glaciers during the Pleistocene epoch.

What is an iceberg?

When an ice sheet meets the ocean, chunks of ice at the seaward end of the glacier will break off over time. This process is called calving. The calved masses of glacial ice are referred to as icebergs. Some icebergs are tabular in shape, with steep sides and a flat top, while others are more irregular in shape, sometimes having domes and spires. Floating masses of ice must be greater than ~5 meters above sea level in height and ~30 meters to ~50 meters thick to count as icebergs. They also must be at least ~500 square meters in area.

What animals live on glaciers?

While some animals do live on glaciers, glacial ecosystems are dominated by microbes. Methane-producing microbes have been found living under glacial ice. Some microbes can also live within the ice as well. For example, rock-eating microbes have been found living in thin films of water on grains of rocky debris entrained within the glacial ice. Other micro-organisms have been found living in veins separating ice crystals. Some microbes could even live within the ice crystals themselves.

Microbes can also live on the surface of the ice where they play an important role in the mass balance of the glacier. Ice algae, for example, will darken the surface, decreasing the albedo and increasing glacial melting, or ablation. Furthermore, microbes will bind to certain minerals, such as cryoconite, which will also contribute to glacial melting. During the summer months, a type of moss can grow on the surface of glaciers and animals, such as ice worms, can thrive, creating a more complex ecosystem. The ice worms that live on glaciers are adapted to harsh, icy conditions, but otherwise are typical worms (members of phylum Annelida) that are closely related to the common earthworm.

Why are glaciers important for humans?

Glacial till is important for agriculture because it provides fertile soil for growing crops. Glaciers are also a primary source of fresh water in many regions. Glacial meltwater also feeds many rivers, such as the Ganges River. The water from the Ganges River is important in India and Bangladesh where it is a primary source both of fresh water and electricity. The electricity comes from hydroelectric power. In many countries, glaciers are also a source of tourism. As the climate continues to warm and glaciers continue to melt, loss of these benefits will significantly impact the people who have depended on glaciers for fresh water, electricity, and other necessities.

What are the benefits of glaciers?

In addition to providing a regular source of fresh water for drinking and for rivers, glaciers also enforce a buffer on the rise in the global temperature. The high albedo of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, for example, reflect a lot of the sun’s light, keeping the planet cooler than it otherwise would be. As these ice sheets melt, the albedo of the poles and Earth’s overall albedo decreases dramatically. This creates a positive feedback loop which leads to even more warming and thus more melting.

Similarities between ice caps and glaciers

Ice caps and glaciers are both masses of flowing ice that can cover thousands of square kilometers.

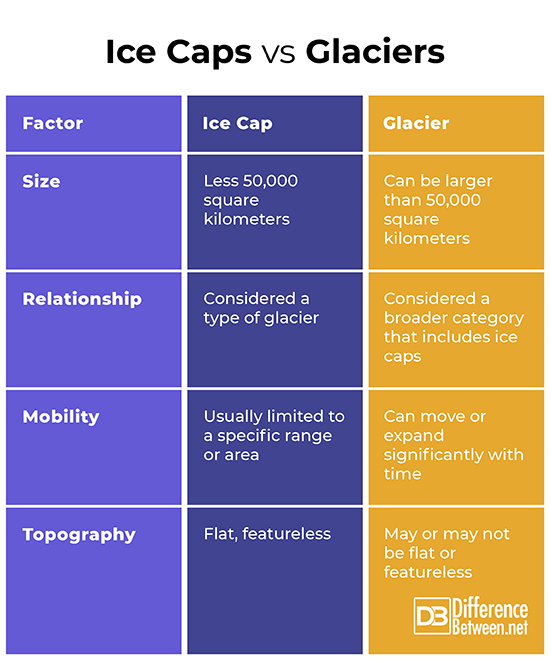

Differences between ice caps and glaciers

Are ice caps and glaciers the same?

Ice caps and glaciers are similar, but they are not the same. They have important differences which include the following.

- Ice caps are always less than 50,000 square kilometers across, whereas glaciers can be much larger.

- Ice caps are technically a type of glacier, whereas glaciers are a broader category referring to many landforms made of flowing ice.

- Ice caps will usually be restricted to a limited area, whereas glaciers will expand more or move more with time.

- Ice caps will tend to have a flat topography, whereas glaciers can occur on slopes and have a rougher topography.

Ice caps vs. glaciers

Summary

Ice caps are domes of ice that flow outward laterally that are less than 50,000 square kilometers in size. They are similar to ice sheets except they are smaller. Glaciers are masses of ice that are large enough to flow with time under their own weight. They can be divided into alpine glaciers and ice sheet glaciers. Ice sheets will tend to be flat and can span continents. Alpine glaciers will be smaller and can exist on a sloped surface. Alpine glaciers can also significantly alter and sculpt the landscape. Glaciers also are home to many micro-organisms and some animals, such as ice worms. Ice caps and glaciers are similar in that they are both large masses of flowing ice. They also differ in important ways. Ice caps are less than 50,000 square km in size. Ice caps will also usually flow within a limited range or area. Furthermore, ice caps are technically a type of glacier, while glacier is a term for a broader category that includes ice caps. Ice caps will also usually be flat or featureless in their topography. Other Glaciers, on the other hand, can be larger than 50,000 square kilometers. They also tend to be more mobile and expand more than ice caps. They also can be either topographically flat or they can exist on slopes and in rugged terrain.

- Difference Between Environmental Performance Index and Development - November 24, 2023

- Difference Between Environmental Intervention and Development - November 8, 2023

- Difference Between Eco Efficiency and Eco Effectiveness - September 18, 2023

Search DifferenceBetween.net :

Leave a Response

References :

[0]Edwards, Arwyn. “Glacier ecosystems.” AntarcticGlaciers.org, http://www.antarcticglaciers.org/glacier-processes/glacier-ecosystems/. Accessed 25 Jun. 2021.

[1]“Glacier.” National Geographic, 21 Jan. 2011, https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/glacier/#:~:text=Encyclopedic%20Entry%20Vocabulary-,A%20glacier%20is%20a%20huge%20mass%20of%20ice%20that%20moves,and%20move%20downward%20through%20valleys.

[2]“Glacier Types: Ice caps.” National Snow & Ice Data Center, 16 Mar. 2020, https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/glaciers/gallery/icecaps.html.

[3]“Ice cap.” National Geographic, 17 Aug. 2012, https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/ice-cap/.

[4]“ice cap.” National Snow & Ice Data Center, n.d., https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/glossary/term/ice-cap.

[5]“Ice Sheets.” NASA Global Climate Change, n.d., https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/ice-sheets/.

[6]Jiskoot, Hester. "Dynamics of glaciers." physical Research 92.B9 (2011): 9083-9100.

[7]Pelto, Mauri S. “Ice Worms” NORTH CASCADE GLACIER CLIMATE PROJECT, https://glaciers.nichols.edu/iceworm/. Accessed 26 Jun. 2021.

[8]“Quick Facts on Ice Sheets.” National Snow & Ice Data Center, n.d., https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/quickfacts/icesheets.html.

[9]Smith, Espirit, “The Anatomy of Glacial Ice Loss.” NASA Global Climate Change, https://climate.nasa.gov/news/3038/the-anatomy-of-glacial-ice-loss/. Accessed 26 Jun. 2021.

[10]Turton, Steve. “Why is the Arctic warming faster than other parts of the world? Scientists explain.” World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/climate-arctic-glacial-melt-rate. Accessed 26 Jun. 2021.

[11]Voosen, Paul. “Record-shattering 2.7-million-year-old ice core reveals start of the ice ages.” Science, 15 Aug. 2017, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/08/record-shattering-27-million-year-old-ice-core-reveals-start-ice-ages. Accessed 25 Jun. 2021.

[12]“What is an iceberg?” National Ocean Service, 26 Feb. 2021, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/iceberg.html.

[13]“Ice cap.” National Geographic, 17 Aug. 2012, https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/ice-cap/.

[14]Image credit: https://live.staticflickr.com/1158/1444110196_435286ee15_b.jpg

[15]Image credit: https://live.staticflickr.com/2542/3852645462_8cd0037c7c_b.jpg